Archive Classics for European Arthouse Cinema Day

• EACD

• Programming

European Arthouse Cinema Day (EACD) is a great opportunity to experiment with your programme and offer your audiences the chance to watch something different. This year’s EACD is fast approaching – the 10th edition will take place on Sunday 23 November 2025 – but there’s still time to book in some special screenings to mark the occasion!

International archive titles are one easy way to enhance your programming, allowing you to explore Europe’s cinema history, tap into growing audiences for repertory titles, and to draw powerful parallels between past and present. Thanks to the Polish, Hungarian, and Estonian Film Institutes, a catalogue of titles is currently available for booking at reduced rates for the 10th European Arthouse Cinema Day participants. Combining established classics with cult gems and rediscoveries, the selection is full of inspiring ideas for alternative programming.

Below we’ve picked out a few highlights from the catalogue to get you started!

Critically Acclaimed Classics

Among the films available to book are some essential titles from the cinema canon.

Andrzej Wajda’s groundbreaking Second World War drama “Ashes and Diamonds” (1958), and Jerzy Kawalerowicz’s seminal “Night Train” (1959), highlighted by Martin Scorsese as one of his “Masterpieces of Polish Cinema,” are both seminal archive titles from major directors well known on the international arthouse circuit.

This year also marks the centenary of the birth of Wojciech Jerzy Has, the Polish auteur best known for “The Saragossa Manuscript” (1965). However, there’s much more to Has than one brilliant film, and the catalogue includes two great examples of his early work: lyrical romance “Farewells” (1958) and wistful drama “Goodbye to the Past” (1960).

Károly Makk’s “Love” (1970), a wrenching drama about the wife of a political prisoner set in the aftermath of the 1956 revolution, is widely celebrated as one of Hungary’s finest films. Another key name in Hungarian cinema is István Szabó. His film “Father” (1966) is an aching, autobiographical portrait of a fatherless child growing up in the 1950s, which deserves to be ranked alongside the great coming of age classics.

Less well known, but just as worthy of a place in the canon is Arvo Kruusement’s “A Woman Heats the Sauna” (1978), a superb social-realist portrait of a Tallinn factory worker struggling with the impossible expectations of Soviet-era womanhood.

Cult Curios

Genre mashups, mind-expanding adventures and journeys into the unknown – cult cinema can provide an amazing portal into the archive, to both new audiences and cult cinephiles.

Although much loved in Poland, where it was a box office hit, “Sexmission” (1983) is ripe for rediscovery elsewhere for sci-fi fans. An offbeat comedy about two men who wake up in a matriarchal future ruled entire by women, Juliusz Machulski’s film pushed the boundaries of satire under Communist rule and remains a subversive treat.

A similarly unexpected take on sci-fi is Estonian filmmaker Grigori Kromanov’s “Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel” (1979), a mystery noir with an extraterrestrial twist in which detective called to a remote Alpine hotel becomes caught in an increasingly surreal sequence of events.

There’s more offbeat, uncategorisable fun in Béla Ternovszky’s “Cat City” (1986), an epochal work of Hungarian animation which riffs on US pop culture – most prominently Star Wars and James Bond – as well as elements of film noir, disaster movies and vampire films, to create a wildly imaginative animated adventure.

Fans of the latest wave of feminist horror led by filmmakers such as Julia Ducournau and Coralie Fargeat, should check out Agnieszka Smoczyńska’s “The Lure” (2015), an impressively inventive musical horror about two murderous mermaids who become performers in a Warsaw night club.

Centring Women’s Stories

Restored work by female directors feature prominently in this selection, offering lots of opportunities to centre women’s stories and perspectives.

Leida Laius, one of Estonia’s most renowned filmmakers, made powerful, emotionally resonant work exploring themes around motherhood, alienation and family. The recently restored “Smile at Last” (1985, co-directed with Arvo Iho) is a sensitive, social realist drama about a teenage girl navigating first love in an orphanage, while her seventh and final film, “A Stolen Meeting” (1988), is the epic story of a woman recently freed from prison in Russia, who returns to Estonia in search of her son.

Ildikó Enyedi is well known on the international festival scene for films such as “On Body and Soul (2017) and most recently “Silent Friend” (2025). Her magical 1989 feature “My Twentieth Century” (1988) a visually stunning historical epic set in turn of the century Budapest, is a magical example of Enyedi’s singular style.

The recent death of Judit Elek in October this year, has rightly drawn attention to the Hungarian filmmaker’s cinematic legacy. Her debut feature “The Lady from Constantinople” (1969), a charmingly surreal story about an elderly woman who swaps apartments, is a fitting introduction to Elek’s gentle wit and poetic approach.

Censorship and Resistance

At a time of great turmoil, historical films can offer inspiring examples of artists calling out oppression and reflecting difficult political realities. These collections include many filmmakers who resisted censorship and made bold statements with their work, often at great personal cost.

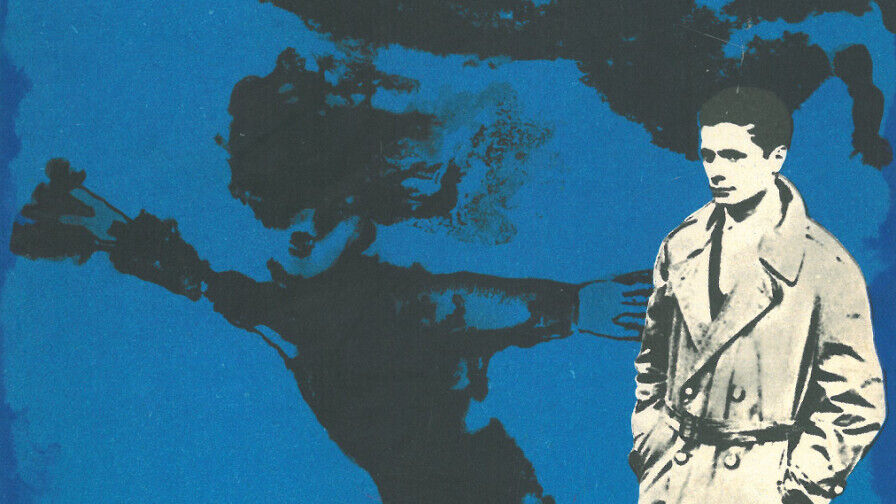

Jerzy Skolimowski’s “Hands up!” (1967) for example, was withheld from release for 14 years, because of the controversy generated by the filmmaker’s bleakly honest depiction of a generation raised under Stalinism. Finally released in 1981, the film is now celebrated as a landmark of Polish political cinema.

With the likes of “Green Border” (2023), Agnieszka Holland has also built a formidable reputation as a fearless critic of injustice and state oppression. Her feature debut “Provincial Actors” (1978), which delivers a barbed critique of Communist-era Poland through the metaphor of a beleaguered theatre troupe, demonstrates that this political commitment has been present in her work from the very beginning.

Another filmmaker celebrated for his humanist approach to political issues is Hungarian director Zoltán Fábri, whose films often depict ordinary people facing profound ethical dilemmas. “Professor Hannibal” (1956) about a teacher who becomes the subject of right-wing hysteria, is a timely story of reactionary politics and mob justice with clear parallels to today which will not be lost on audiences.

The full list of titles available for booking, along with terms and additional information, can be found at the link below.

11.11.2025

Rachel Pronger

Rachel Pronger is a writer, curator and editor based in Berlin. She began her career working for festivals and cinemas across the UK, including Tyneside Cinema, Edinburgh International Film Festival and Alchemy Film & Arts. She has served as a programme advisor for Sheffield DocFest, BFI London Film Festival, Alchemy Film & Arts and Aesthetica Short Film Festival. Her writing on film and visual art has been published by outlets including Sight and Sound, Documentary Magazine, The Guardian, MUBI Notebook, Art Monthly and BBC Culture, and she is the co-editor of online journal Cinema of Commoning. Rachel is also the co-founder of Invisible Women, an archive activist feminist film collective which champions historic work by women and marginalised gender filmmakers through curation, events and editorial. more from the author