Keeping Cinema Alive in a Conflict Zone

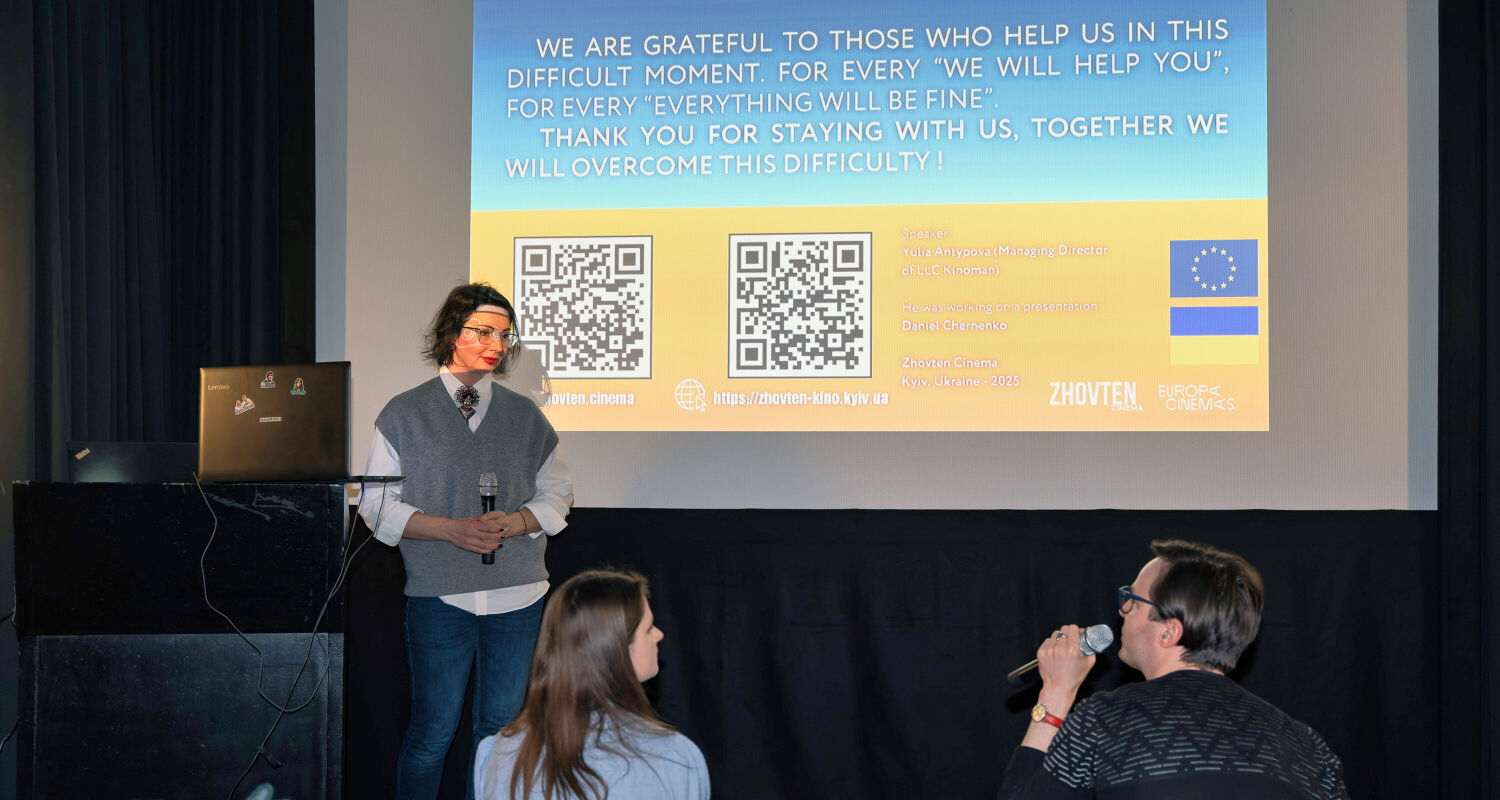

Yuliia Antypova, Zhovten Cinema's director, holding a presentation about the Zhovten during the CICAE Arthouse Cinema Training Alumni meeting at Brotfabrik during Berlinale

Cinema's resistance

What role can cinema play in times of war? Even in the most extreme of situations, when a country is in a state of emergency, culture still has a role to play. Cinema especially, can often hold a special place in the “cultural front”, providing a space for communal gathering, psychological support and escapism for citizens during wartime.

This has certainly been the case in Ukraine where, since Russia’s full scale invasion in February 2022, many cinema workers have strived to provide a safe and welcoming space for visitors the face of air raid sirens and bombardment. One such example is Zhovten in Kyiv, where since the war began cinema director Yuliia Antypova and her team have being doing everything they can to keep the doors of the city’s oldest arthouse cinema open. Founded in 1931, this six screen multi-arts venue is a much loved fixture in Kyiv’s cultural scene, and for Antypova and her colleagues, ensuring the continued operation of this historic building has become a vocation.

“ It's very important to continue our work, in order to help our fellow Ukrainians, to survive this war,” says Antypova. “In a way, the culture of the nation is shaped here. Zhovten is a multi-functional cultural center that combines cinema with other forms of creativity, creating a space for the exchange of ideas. The cinema creates a bridge between different artforms, uniting people around common values, concepts and aspirations. In the 94 years we have been running, we have never changed this goal. ”

Resilience

That long history, and the many crises Zhovten it has lived through during its decades of operation, serves as an inspiration to the cinema’s team. Antypova points out that even during the Second World War, cinemas served as a vital source of community and support for citizens on the home front. “We have to continue working, because life goes on,” she says. “We need money to live, but the work also helps us to forget a little the awful things around us. A lot of people go to the cinema to support one another. We are all waiting for this moment when we might move beyond the war. When there is a deadly bombardment in the city, less visitors come, but after two or three days, people start to want to come back to the cinema. They need to forget the situation for a little bit.”

In the immediate aftermath of Russia’s full scale invasion, Zhovten closed for three months, but by 12 May 2022 the cinema had reopened. Since then, demand has steadily risen. Since the beginning of the war until the present day, the cinema has hosted approximately 30,000 film screenings, and attracted more than 500,000 viewers. Although the first year of war-time operation was very difficult, with the cinema forced to take on credit in order to stay open, audiences have continued to grow. Interestingly, visitor numbers for 2024 into 2025 actually suggest an overall increase in attendance, compared with figures from 2019, the last pre-Covid, pre-war period in which the cinema could be said to have enjoyed “business as usual.”

Daily Operations

This level of visitor engagement is all the more remarkable when reflected through the practical challenges the cinema faces on a daily basis. The constant threat of attack, air raids and regular energy shortages have become part of life for cinemas still operating in Ukraine. At Zhovten, every time the air raid alert sounds (in Kyiv this often happens multiple times a day), the film is paused and the cinema evacuated. Once the threat has passed visitors can return to the auditorium, where the film is resumed. Given that screenings might often need to be cancelled at short notice, and that late evening and nighttime screening slots are no longer possible, Antypova and her team have had to take a flexible, creative approach to scheduling. They have also rented a generator to ensure screenings can continue even during power cuts

A notable way in which the war has affected the tastes of Ukrainian cinema goers, is in a growing interest in national cinema, both contemporary and historical. The team at Zhovten has seen a dramatic increase in interest in Ukrainian made films since reopening, and have responded with programmes centring seminal national filmmakers such as Sergei Parajanov. “The younger generation is eager to familiarize themselves with their cinematic heritage,” says Antypova. “We feel sure that now is the time for culture, the time for cinema. It’s time to study our classics, and read, listen and watch the Ukrainian canon. It’s time to cultivate spaces that allow us to collectively live and experience our culture, and to support contemporary artists who tirelessly record the reality of war in their work.”

Ukrainian Cinema

Those contemporary artists have also demonstrated how film can serve as a powerful tool for sharing Ukraine’s story internationally. Over the past few years, a wave of notable Ukrainian films have appeared widely at festivals and award ceremonies around the world. The high profile success of documentaries such as Mstyslav Chernov’s Academy Award-winning 20 Days in Mariupol, is an indication of the role cinema has been playing in charting the horrors of war, and in elucidating the political and historical factors which have created this current situation. That filmmakers continue to produce work in the face of collapsing infrastructure, as well as great personal loss, danger and trauma, is exceptional on its own terms. That remarkable achievement was acknowledged in 2022, when the European Film Academy and Eurimages dedicated that year’s Eurimages Co-Production Award collectively to all the producers of Ukraine. The importance of contemporary Ukrainian productions to the global film scene has continued even as the conflict has tightened its grip, and can be seen reflected in, for instance, a selection of exceptional films about the war at Cannes 2025.

Film has also played a role in charting Zhovten’s story. The reality of daily life at the cinema over the past two years was powerfully captured in Nadia Parfan and Karina Kostyna’s documentary Le Zhovten de Kyiv, which screened on French television in December 2024 as part of a series on iconic cinemas. Since the outbreak of war, Antypova herself has seized every opportunity to tell their story. “At the start of the war, I probably took part five conferences” says Antypova. “I gave presentations, describing how we were surviving at our cinema, to share our experience and show how difficult it was to live through this and continue to work. I’m very thankful to our colleagues across Europe, not only for their kind words but also for their acts of support. It’s important to call for help and to show people the difficulties you are facing.”

Protecting your people

As the war continues without a clear end in sight, the dedication of the team at Zhovten remains undiminished, a symbol of the wider resilience of the Ukrainian people. When asked what advice she might give other cinemas facing similar circumstances, Antypova’s answer is clear and emphatic. “I would tell others to think about how they can create the safest situation for the people who work for you and for your visitors,” she says. “Sometimes we have to stop the work, and go to a shelter, because life is the most important thing. Not business, not tickets, not money. Have a plan in place and clear instructions. Keep your employees and visitors safe.”

17.06.2025

Rachel Pronger

Rachel Pronger is a writer, curator and editor based in Berlin. She began her career working for festivals and cinemas across the UK, including Tyneside Cinema, Edinburgh International Film Festival and Alchemy Film & Arts. She has served as a programme advisor for Sheffield DocFest, BFI London Film Festival, Alchemy Film & Arts and Aesthetica Short Film Festival. Her writing on film and visual art has been published by outlets including Sight and Sound, Documentary Magazine, The Guardian, MUBI Notebook, Art Monthly and BBC Culture, and she is the co-editor of online journal Cinema of Commoning. Rachel is also the co-founder of Invisible Women, an archive activist feminist film collective which champions historic work by women and marginalised gender filmmakers through curation, events and editorial. more from the author